It is hard to imagine now, but until the early 70s great ships would sail up the Usk in Newport as far as the Old Town Dock, where they would be scrapped. Among them were some of the grandest and most famous warships of the Royal Navy. MARTIN WADE recalls the great fighting ships which met their end at Cashmores.

Cashmores was a Newport firm whose name would have been known throughout the world as the place where ships came to die. Some of the biggest ships of the Royal Navy came here to be broken up when they were too old to fight on or peace meant they were no longer needed.

The West bank of the Usk has changed so much on the last 50 years that it is difficult to work out where these great ships were broken up. If you're looking for it today, when walking away from Newport, past Castle Bingo it's just past George Street Bridge.

And there, vast battleships and humble minesweepers met their end by cutting torch and were reduced to piles of broken metal.

Many great ships were taken to Cashmores at the end of the First World War. Millions had been spent on ultra-modern ‘Dreadnought’ battleships in the first decade of the century, but they were soon outclassed.

One of the largest warships to be scrapped at Cashmores was HMS Collingwood. Launched on 7 November 1908 and completed in April 1910 she cost around £1,600,000. The ship was deemed obsolete after the war; she was reduced to the reserve and used as a training ship before being sold for scrap in 1922.

Many ships scrapped there were built to fight in the Second World War and when peace came were surplus to requirements.

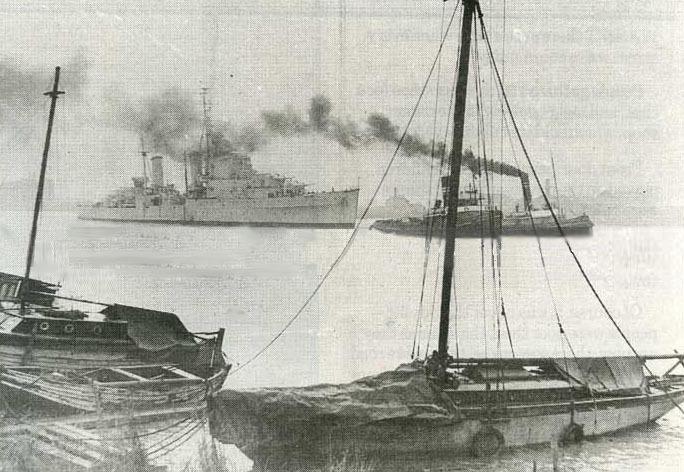

One of these was HMS Enterprise. She came to Newport soon after the war in 1946 and made a great impression on those who saw her.

The cruiser bristled with weaponry, with seven six-inch guns, two four-inch and 16 smaller guns. Although now this once lethal ship was a force no more and her guns would never fire again.

The sight it was said, filled spectators with a mixture of "pride, regret and almost sorrow" for the ship's crew stayed with her on her final journey and were mustered on the deck of the Enterprise, standing stiffly to attention as the Union Jack and the Naval Ensign were lowered for the last time.

It was to be the final act in a glorious career. In 1940, she had battled her way out of Narvik with the Norwegian government's gold on board as the invading Germans closed in on the besieged town. She had fought eleven German destroyers in the Bay of Biscay, sank three and damaged two others before the rest escaped. She had the honour of having the Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill aboard when she took part in the bombardment of the Normandy coast on D-Day.

The Enterprise was seen as a lucky ship. Throughout the war she never received a damaging hit and only two members of the crew sustained wounds. Perhaps in recognition of this she had sailed from Portsmouth manned by her full crew.

Some ships had distinguished war careers and then continued to play a useful role. HMS Verulam had battle honours stretching from the Artic, to Normandy and Burma. Her greatest moment came in the Battle of the Malacca Strait when she helped sink the Japanese cruiser Haguro on 16 May 1945.

After the end of the war she saw service preventing Jewish immigration into Palestine in 1947. She then played a number of roles in training and research before finally being paid off in 1970 and setting sail for the last time as she made her way to Newport.

One Argus reader had very poignant memories of her coming to Newport to be broken up. Dale McCollum worked at Cashmores from 1970 to 1972 and in October that year, the Verulam arrived for breaking. He had served on one of her sister ships and walked onboard the doomed frigate before the work began in earnest. The effect was eerie: "I was surprised to find that it was almost as though the ship's company had gone ashore and would be returning any minute. The only thing missing seemed to be the personal effects of the crew, but otherwise she was intact."

Tony Whitcombe was an electrician at Cashmores between 1968 and 1976. He worked on HMS Manxman and remembers her well. "She was the fastest ship in the Royal Navy during the war. We were told all about her before she came to Newport."

The Manxman was one of the last Royal Navy ships to be scrapped at Cashmores. Tony has some fond memories and souvenirs of the ship.

She had seen service delivering mines to the Russians in Murmansk and later running supplies to the besieged island of Malta. Her top speed of 40 knots meant she could outrun any U-boat and so often would sail alone, not needing to be part of a convoy.

A fire in the late sixties put paid to her naval career. She was sold for demolition by Cashmores and arrived at the breakers yard in tow on October 6 1972 after 32 years of distinguished service.

Despite her fame, this fine ship was gone in no time. "She only took a few weeks to break up" says Tony. "A team of about 20 with cutting torches set about her."

And so she was dismembered. "The structure above the deck went first." The cutters did their work and a crane lifted it off and so it went on as they devoured the ship, its hull shrinking towards the Usk mud on which it sat. "They would work around the tide" Tony recalls. "They'd cut down so low and when the tide came, they'd stop and wait for it to go out again."

Even though they had to work round the Usk's tidal rhythms they were still quick. "Time was of the essence" Tony says. The quicker a ship could be processed, the quicker another could be cut up to bring more lucrative scrap.

Tony has a memento of the ship still – a chest from the captain’s cabin: “It was lying on the quayside as she was being broken up and the foreman said I could have it. I still use it for storing socks and things. I’m just glad it could be preserved” he says.

She met her end as many ships had been before, but not many came after her. Cashmores only scrapped seven more ships after the Manxman, before the last ship was scrapped in 1976.

Another naval craft which marked Cashmores swansong was the Auriga which came in 1975. Tony went inside the submarine to fit temporary lighting and was moved by what he found. "I sat on the seat which would have been used by the man firing the torpedoes. The space was so small. I'm a little fellow and I found it cramped. 'How on earth did they live like that?' I wondered - and how many times did he fire a torpedo from there?"

He remembers Cashmores as a good employer; it was a company from another era. Most of the board members were members of the Cashmore family. "They were a good company to work for" he says. "If you had a job with Cashmores, you had a job for life."

The tidal range of the Usk is among the highest in the world and this made Newport a place where ships of this size could be sailed and then safely beached for the breaking up to begin.

It was Newport’s melancholy privilege to see these great fighting ships sail gracefully up the river but then to be torn apart as their useful life came to an end.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel