SOMETIMES verbose but often succinct, capable of great insight as well as the most thudding rhyme,William Downing Evans is back among his own people.

Ian Dear, author of more than 20 books mostly about naval or military history, is, with his journalist wife Wendy, responsible for Evans’ literary resurrection.

“Why he has remained obscure is one of those mysteries.

“Isn’t it often the case that the best people don’t rise to the top?” the writers asks, rhetorically.

“The poems capture the essence of Newport at a crucial time in its history – the 19th Century, which sawit grow from a village into a substantial and important town.

“But in thinking about his writing, we should not forget what through his use of statistics my maternal great-grandfather was to do for the town’s poor.”

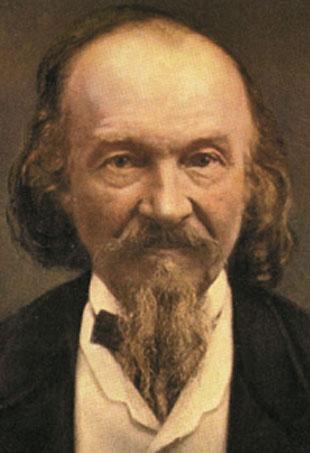

William Downing Evans was born at Caerleon in 1811, the eldest son of a lime burner.

How he acquired his education is not known, although the patronage of the Morgan family and the self-improving ethic of his Baptist faith are likely explanations.

“There are many interesting facets to a man who was at the centre of Newport’s efforts on behalf of the poor for the best part of the 19th Century,” says Mr Dear, who lives in London and who is editor of the Oxford Companion to WorldWar Two and a second edition of the Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea.

“He certainly knewCharles Dickens, who delivered a lecture in Newport in the 1860s.

In fact, the family has the chair Dickens sat on.

“Yet despite his connection with what was then Newport’s workhouse ( later StWoolos Hospital), his only reference to the Chartist rising of 1839 was ‘a disturbance in the town’.”

Acousin interested in family history was responsible for Mr and Mrs Dear plunging into archives and family records and coming up with the gemstone which is William Downing Evans: Poetry and Poverty in Nineteenth-Century Newport.

The book is published by the SouthWales Record Society with the co-opted efforts of Professor ChrisWilliams, a Newportonian occupying a chair of history at Swansea University.

Evans took Leon as his bardic name probably in tribute to Caerleon.

In 1837, he was appointed registrar of births and deaths in Newport and in 1839, was living at Woolaston Cottage, which formed part of the wall of the newworkhouse.

Since the workhouse was one of the Chartists’ targets, this makes his ignorance as to their insurrection even less understandable.

For more than half a century, Evans was clerk to the Poor Law Guardians and a meticulous recorder of statistics which were relentlessly employed when putting his case on behalf of the poor.

Yet it would be for his poems, songs and hymns that most Newportonians would have known him.

His book The Autumn Wind binds together the poetic insight of a nature-lover with the Victorian obsession with death and decay, and throws light into some obscure corners of the city’s history.

Within a short space of time after noting in verse the death of a Waterloo veteran, he was able to dash off a memorium to the assassinated President Abraham Lincoln. Not only people but structures; his Ode to Alexandra Docks must be the most extravagant paen of worship ever written to a very large hole in the ground.

The restless pen was finally stilled in 1897 but as a remembrancer, he is yet to be equalled.

Howelse would we knowof Corporal Thomas Morgan of Tredegar, whose sword “long since rusted in its sheath” died in 1865 having fought atWaterloo 50 years before?

The Chartists may well have gone unremarked by Leon, but by dint of his labours, the likes of poor Morgan – who died in the workhouse – are known.

It is fitting that the poet who illuminated neglected corners of our past should nowhimself be brought into the light.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article