THE grandson of a Newport sailor who stowed away to join the famous Shackleton Expedition to Antarctica retraced his steps as he visited the treacherous polar island where he was stranded. Martin Wade meets John Blackborow.

John Blackborow remembers clearly the last time he saw his grandfather, Perce, the Antarctic explorer from Newport. The three-year-old John was standing outside the house his family shared with Perce. “I was crying, saying I wanted to see him, so I was allowed to go upstairs. He was lying in bed and I walked up and they let me shake his hand. I didn't realise it but he had died not long before."

This is no chilling memory for John. He tells it sat in his study with walls adorned with pictures of Perce while serving in Shackleton’s Antarctic Expedition. Hurley’s famous picture of him with the ship’s cat Mrs Chippy on his shoulder takes pride of place among many others. Perce’s Polar Medal too is kept safe here, burnished bronze in its worn leather pocket.

Perce was one of the 28 men, led by Sir Ernest Shackleton, aiming to be the first to cross the frozen continent. Their two-year odyssey saw them forced to abandon their ship after it was trapped in ice and then live on ice floes before sailing in open boats to Elephant Island.

The uninhabited island, scoured by 100mph winds, was home to the men for four months as they waited for rescue. Here, Perce had the toes of his left foot amputated after they became frost-bitten.

Few people have been back to Elephant Island. Some of the Endurance’s crew briefly returned in 1922, scientists make occasional visits.

So it was a rare honour when John was offered the chance to travel to the Antarctic in 2002 with the McKelvey expedition in 2002. He was invited with two other descendants of expedition members; Peter Wordie (son of James Wordie, the expedition geologist) and Phillip Shackleton, Sir Ernest's nephew.

They travelled in a modern Russian icebreaker, capable of pushing great floes of ice weighing hundreds of tonnes. Just under 100 years earlier, the Endurance was eventually snared by the kind of ice this monster would brush aside.

"We found the spot on Elephant Island where they had lived for those long months" John recalls, but we couldn't quite reach where they camped."

"It's hard to describe how it felt. We visited in January in the middle of summer down there. You still had to be careful taking a glove off because it was bitterly cold, but they went through a winter."

"I kept thinking 'how did they do it?'" We were there in this great ice-breaker, well-fed and wearing modern clothes - all the things they didn't have."

The men who endured months on this frozen hell-hole did so with clothes which were constantly wet. Their meagre rations were eaked out with the occasional seal or penguin. On the day they were rescued, the cook was boiling up a seal's backbone with some seaweed. They would not have lasted much longer.

The three of them, separated by just a generation or two from this heroic feat could only gaze at this bleak place and wonder how on earth they had managed to survive.

John has reason to be awe-inspired. An experienced sailor, he works with Challenge Cymru a yacht which sails around the British Isles giving youngsters a taste of life at sea.

"The thing about sailing is that you see people's character very quickly. You can't get off a boat - you've all got to get along."

What if true now was even truer for Perce and the other 27 of the Shackleton Expedition. Stranded on ice for months, enduring harrowing journeys in an open boat in the Antarctic winter, then living on a blizzard-lashed polar island - they all had to get along.

He adds: "But no matter how bad it gets, I always think: 'This is nothing to what Perce put up with.'"

Was there something special about that time? Have those qualities disappeared with Perce's generation and the last age of heroic explorers? John doesn't think so.

"It was a staggering achievement, but a man was found last year who survived 483 days adrift at sea.

"It shows that kind of spirit still exists."

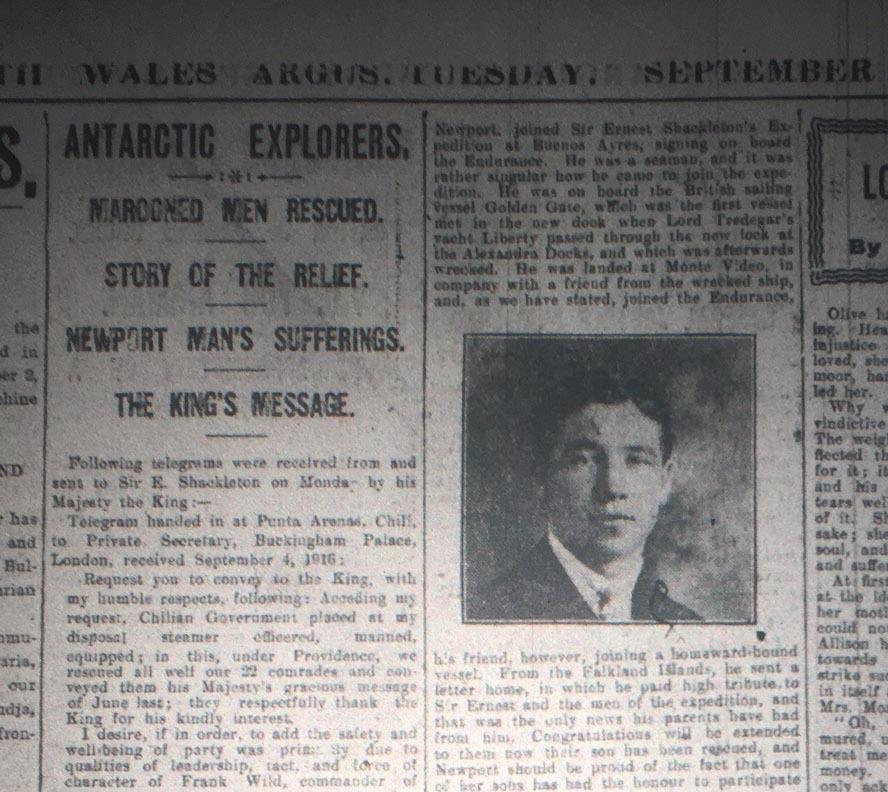

The Argus reported on the plight of the expedition in July 1916. When the party led by Shackleton reached South Georgia and sent news home, the paper had a picture of Perce, telling how he was one of Sir Ernest’s men "presently stranded on Elephant Island".

By September 5 the paper could break the news of the men's safe return and tell how Newport should be "proud of the fact that one of her sons has had the honour to participate in such an heroic enterprise".

But Perce was a modest hero. When crowds waited at Newport station to welcome him home, he crossed the tracks and took another route home.

“The first house we lived in Newport was with Perce in Maesglas”, John recalls: “My father, Jim Blackborow would say he was very quiet about things, But when he spoke you had to listen to him.”

The only time he talked at length about his time in the Antarctic was to speak to the YMCA Boys Club in Newport.

And here he merely hinted at the hardship they faced. As they crossed the frozen seas to reach the haven of Elephant Island he told the boys of “going through a bad time with low temperatures and about 8ozs food daily rations”.

But his description of Shackleton, or ‘The Boss’ as he was known to the men stands out.

“He had a genius for keeping men in good spirits, and need I say more, we loved him like a father.

“He was a tall, broad-shouldered man, possessed of a very generous nature with which he combined extra-ordinary powers of endurance and hardihood. He was optimistic even when things looked blackest, this inspired those who served under him.

“These attributes and what he had accomplished made him, I think, one of the greatest explorers in history.”

John echoes that point: "Shackleton's achievement was that he kept the men together. It was his genius that kept them together.

"There was a point where McNish the carpenter was about to mutiny, but Shackleton stopped it. Later McNish would save their lives by fixing the boats so they could sail in the open seas."

In turn, the skill and leadership of Shackleton and their leader on Elephant Island, Frank Wild and Wordie saved the men in the island - and of course James McIlroy the surgeon saved Perce too. “Without them all” John says, “Perce wouldn't have lived and I wouldn't be here!"

The fact that Perce remains unknown to many in Newport is something John would like to change. “For what he achieved, for the great story he was part of – I think he should be remembered in Newport, perhaps with a blue plaque. He shouldn’t be forgotten.”

But for John, the man whose hand he shook as the life slipped from him, a hero of an heroic age, will always be remembered.

Newly digitised images of the Endurance expedition which tell this story of human survival are now on display at the Royal Geographical Society. The photographs, taken by Frank Hurley, reveal previously unseen details of the crew’s epic struggle for survival both before and after their ship was destroyed.

The Enduring Eye exhibition opened to the public on Saturday 21 November, exactly 100 years to the day that the crushed Endurance sank beneath the sea ice of the Weddell Sea, and runs until 28 February 2016.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here