A GLANCE at any newspaper from a hundred years ago would seem to tell you that they were there only to advertise. News did not appear on the front page until the 1930s and since then, Martin Wade tells how Argus adverts have changed radically just as technology and tastes have altered.

ADVERTISING as we know today has its roots in the industrial expansion of the 1880s. The mass production and cheapness of consumer goods meant more things were available to more people than ever before.

For much of the 19th century, bill-posting was the preferred method of advertising.

Newspaper adverts were subject to a tax while bills were not, and they reached a wider audience.

Just as today there is resentment at ‘A’-boards in streets and hand-bills being thrust at shoppers, so there was in the mid-1800s when bill-posting reached a peak.

Then, walls would be covered with tattered posters.

This led to some self-regulation with specific hoardings provided for bill-posting.

But tax changes meant newspaper advertising would replace bill-posting as the preferred method of talking to the Victorian customer.

The abolition of the advertising tax in 1853, the duty on newspapers in 1855 and on paper in 1861 were massive boosts for advertisers and newspaper publishers.

It was into this new arena that the infant Argus stepped in 1892.

Advertising then became front page news, literally.

For the first 40 years of its history, the Argus, in common with most newspapers, carried only advertising on the front page.

The broadsheet would be covered in densely packed advertising type.

Many British publishers, including Lord Northcliffe of The Daily Mail refused to allow large fonts.

He complained his advertising manager was "a damn nuisance" for trying to put large "garish" type on his front pages.

Some advertisers, told to only use small type, would fill entire pages with endless repeats of the same slogan, or creating large letters out of small ones.

Nevertheless, the Argus front pages until the 1930s were crammed with small text advertising such bargains as this in 1892: "For Sale Handsome Walnut Piano, with all the latest improvements, double action, full compass. Price Eighteen Guineas – cost £45 – Ede's Old Curiosity Shop, Newport.

Houses too were a snip in those days. How much would this get you today? "To Let 2 houses, Bryngwyn Road and Clytha Park, £45 and £50 per annum respectively. Clyde Bank Villa, Manley Road, £25 per annum; Clifton Villa, Chepstow Road £42 per annum."

Other papers were reluctant to change. The Guardian (then The Manchester Guardian) did not put news on its first page until 1952, and even then its editor, AP Wadsworth, only did this reluctantly. "It is not a thing I like myself,” he said. “But it seems to be accepted by all the newspaper pundits that it is preferable to be in fashion."

The Dundee Courier kept up the practice of giving over its front page to classified advertising until 1992.

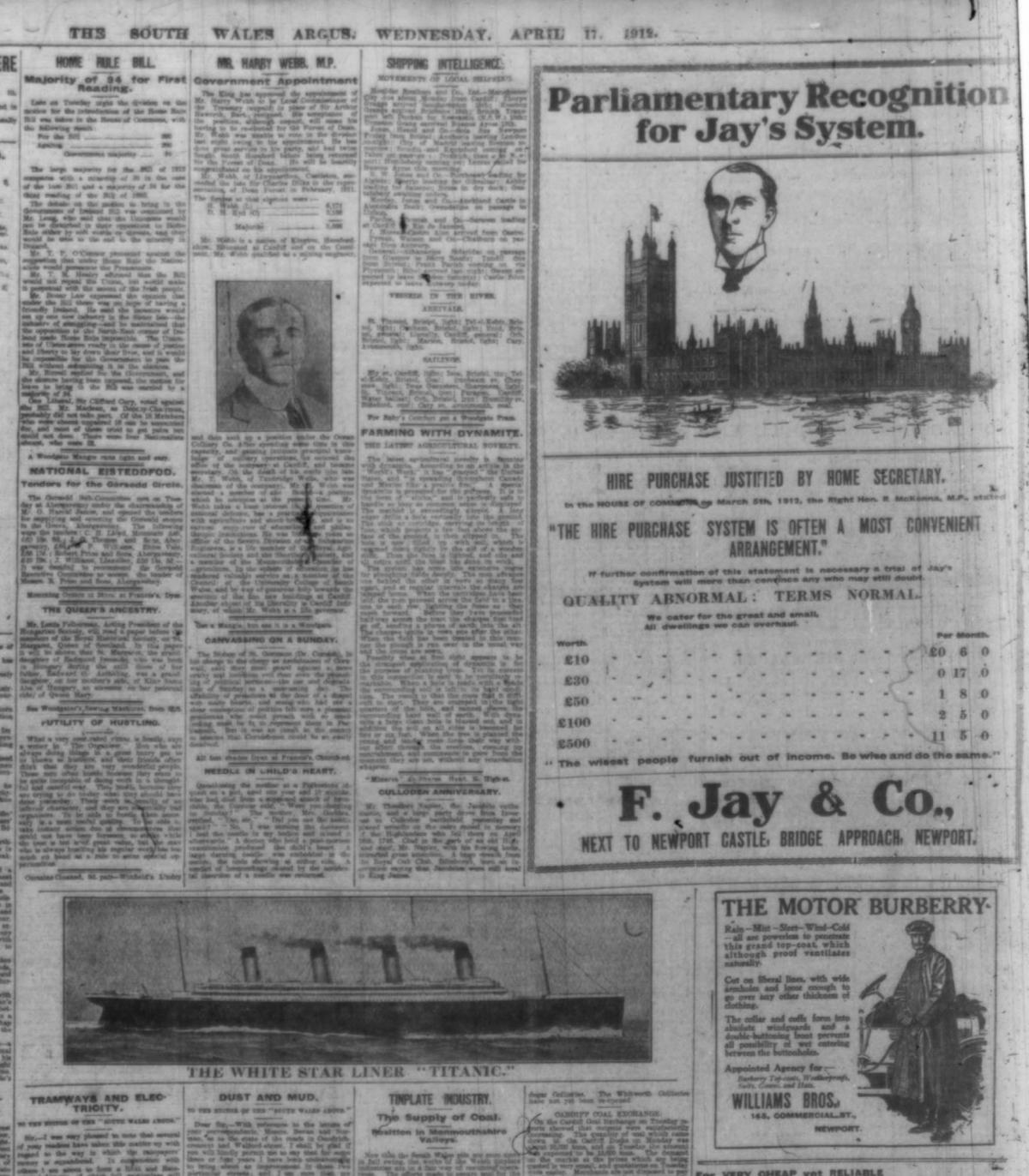

It seems incredible to our eyes to see a page like that in 1912 when the Argus reported the sinking of the Titanic.

The most eye-catching part is the ad for Jay's furniture store on Bridge Street in Newport.

This reflected the position of advertising in newspapers generally, but also the technology of the day.

The advertisements here would be have been created well in advance. The drawing would be copied onto a block of wood. All the surface except the lines to be printed would be cut away. In these pictures shadows were represented by small separate strokes.

The carved block would then be pressed into clay, making an impression of the image. Then molten metal was then poured onto the clay making a cast which would be used to print the image on a page.

Pictures would have been created using the more modern halftone system which prints images as a series of dots.

From the 1890s newspapers were printed using hot metal typesetting.

This method injects molten type metal into a mould into the shape of letters. The cast metal elements are later used to press ink onto paper.

Pictures, like that of the Titanic, would be more difficult to produce quickly. By the 1930s, a technology called wirephoto meant pictures could be transmitted. The machines were very large and expensive and required a dedicated phone line. Only news media firms like Associated Press could afford to use them. Pictures had only recently began to be used in newspapers.

Advances in technology meant photographs could be used more readily. In 1946, the Argus adopted a process called photo engraving. Here a photograph would be projected on a sensitized metal plate, which was then etched in an acid bath. This led to a much wider use of pictures.

This meant a front page ad from 1946 for 'Phyllosan - the tonic to revitalize the blood and strengthen the nerves’ could have a picture showing an elderly gent, the type whom the ad was aimed at.

By 1979 another advance in technology saw the Argus use photocomposition where the elements of a page were photographed onto film from which printing plates were made.

An ad for KQ furniture shop on Clarence Place in Newport shows how this could be used.

Now pictures and graphics could be added to make ads like stylish ads this one.

The furniture shown is quite possibly back in fashion now, even if the prices are not.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel