ALL that stands there now is a car park and a Travelodge but once it was the site of Newport's grandest building where thousands were spell-bound by cinema, theatre and the stars of the day. Martin Wade recalls Newport's Lyceum Theatre.

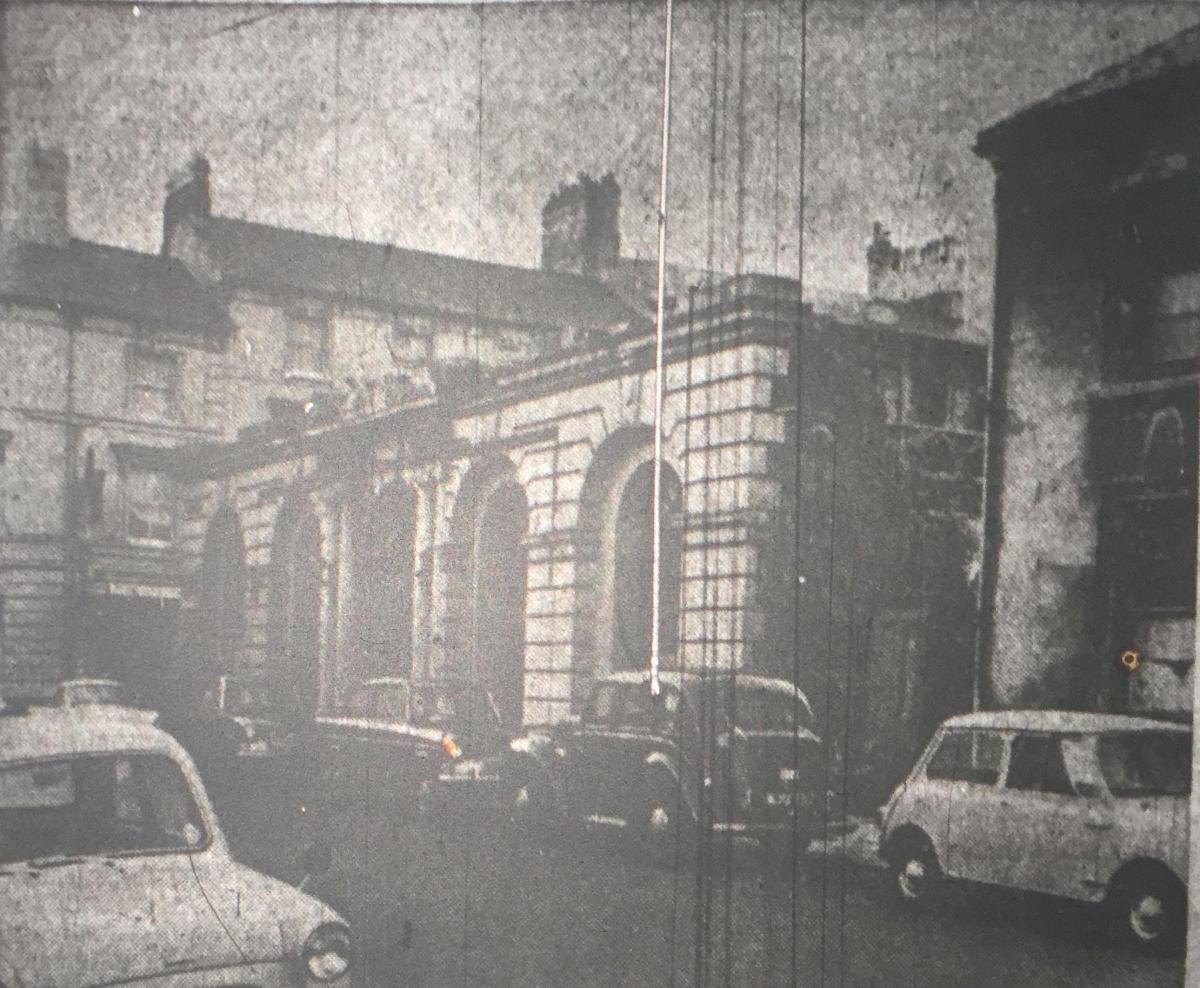

Its grand, classical facade and graceful pillars supported a statue of Queen Victoria. It spoke of confidence in its role of bringing art to the people. The Bridge Street theatre would not have looked out of place in a European capital or maybe even Greece itself.

Thousands of Newport people had been entertained in the seats of the Victoria Hall in the years since it was built in 1867. This impressive building also held the County Court, Turkish baths, swimming baths, gymnasium and a reading room.

Designed by architects Habershan and Pite of London it was built by Henry Pearce Bolt of Newport. Its £12,000 price tag paid for such luxuries as using carved stone for mouldings instead of plasterwork. The most famous of these was the great statue of Queen Victoria.

But one May night in 1896, fire tore through the magnificent theatre.

The blaze broke out after the last performance of the evening had finished. The fire brigade's hoses could not shoot water up to battle the inferno. The flames licked as high as the statue of Queen Victoria, which onlookers said seemed oblivious to the fire. The timbers of the roof collapsed and it seemed the theatre would be lost.

But ten hours later when the fire was out, it was clear enough of the building had been saved.

The Victoria Hall and later theatre was impressive enough, but what would rise, phoenix-like from the smouldering timbers of the Victoria would be even more impressive.

The ruins of the old building were bought by Clarence Sounes, an impressario who also owned the Grand Theatre in Cardiff and the Queen's Theatre in Birmingham.

Sounes wanted the new theatre to be “among the best in the kingdom”, and he commissioned WR Sprague, the well-known theatrical architect, to prepare plans for a new building.

Sprague specialised in designing music halls and theatres. Working in the last decades of the 19th Century, business was good. Many of his designs still stand and most are in London's West End. The years between 1895 and 1905 saw him create many handsome playhouses which still work today. Some are iconic West End theatres like the Gielgud, the Novello and the home of Agatha Christie's 'The Mousetrap', St Martin's. Many are listed and deservedly so. But that protection was never given to Newport's own theatrical icon.

Sprague wanted the existing Grecian style of the Victoria Theatre be preserved. The new would be created within the walls of the old. This made his design for the enlarged Lyceum Theatre unique among his work.

Newport builder John Linton was tasked with the reconstruction. Safety as well as style now governed the construction. Newport Borough Council insisted new internal walls should be built to prevent any of the old ones giving away. Although Sprague's buildings were noted for their classical finesse, much of his thought went in to making the building safe, especially after its predecessor was gutted by fire.

To guard against the risk of flame, the whole of the auditorium was built of iron and concrete, with woodwork only used for doors, fittings and seating. The wooden floors were laid on concrete.

A fireproof curtain made of asbestos and iron which could be lowered in four seconds was fitted. Careful consideration was given to how the audience could escape in the event of a fire. There were six exit doors from the stalls and pit alone, and with fire exits from the dress-circle, balcony and gallery, it was estimated that the building could be emptied in three or four minutes. Fire hydrants were fitted throughout.

The £20,000 it cost to build paid not only for the structural changes, but its sumptuous decoration. The fittings were of a Renaissance style in cream and gold. The dome, 65 feet above the orchestra pit, was adorned with cupids representing the arts. Balconies were decorated with figures and drapes were in a striking peacock blue. Saloons and lounges were richly decorated with ornamental and decorated ceilings; the walls hung with silk tapestries and mirrors. It was the equal of any of Sprague's West End creations.

The site hosted many famous names and fantastic spectacles. As the Victoria Theatre, an early version of film was shown in 1870, when a ‘Phantoscope’ show, or ‘tableaux of illusionary scenes’ was given to no doubt awestruck audiences.

Charles Dickens too appeared there the year earlier when he read from a Christmas Carol and The Trial from Pickwick Papers. The audience were said to be enthralled by his “wondrous facial power capable of most varied expression” and gave him a standing ovation.

When Houdini came to Newport in April 1905, he spent a week performing at the Lyceum. Having finished his residency, he went on to escape from a cell in Newport police station.

Later, with the advent of cinema the theatre would serve Newport as a picture house. There was still room for live drama when stars of the silver screen would make appearances like when Roy Rogers rode down Bridge Street on his white horse and entered the theatre through one of its side doors.

The Lyceum’s live shows continued with ice rinks and even a boxing kangaroo. However it was a venue for pantomime that it is best remembered. And it was a pantomime on which the curtain fell for the final time at the Lyceum.

As audiences dwindled and pressure grew to redevelop Newport town centre, the theatre was closed and the decision taken to demolish it in 1961. Planning permission was given for a seven-storey office block with shops at street level.

The Argus of 20 February that year told how there was a "packed audience" for the performance of Little Miss Muffet, but that the "last sad moments of the Lyceum brought tears in the eyes of many."

As the day it would be pulled down approached, the last owner of the Lyceum, Peter Norman Wright, told the Argus: "I hope that if the name of the Lyceum is remembered, it will not be for the fact that it closed, but that for many years we kept open in the face of great odds."

"Within this most handsome facade, millions have found new worlds after leading their own small world of hard reality outside.

"You may never see it's like again" he warned.

The report said the floodlights outside "continued to cast their yellow radiance on the pillared facade which will soon be rubble."

However, almost two years after the demolition, the site was still unused. The remains of the theatre had become an “eyesore” said the Argus. It was an ignoble end for such a grand building.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel