An act of bravery by a Newport soldier 100 years ago this month saved the lives of many at a notorious army camp, MARTIN WADE tells this fascinating tale of heroism.

It was a notorious army camp where hundreds of thousands of soldiers were trained before they went to fight in the trenches in the First World War. Many there were struck down by disease and it was the site of a mutiny at the end of the war.

But one Newport soldier prevented a tragedy there, nearly 100 years ago to this day, saving lives by his heroism and quick thinking.

Joseph Stokes was a steelworker at the Lysaghts plant in in Newport. When the company moved from its base in the Midlands in the 1890s, Joseph’s father, encouraged by the promise of a job and a house, had walked from his home in Walsall to Newport in order to find work there.

His grandson Graham Stokes tells how the promise made by the Lysaghts firm was made good. “He lived on Portskewett Street, which was built for the Lysaghts workers.”

When war came in 1914 Joseph joined the South Wales Borderers. He was part of the 6th (Service) Battalion (Pioneers) of the famous regiment. It was their job to dig trenches, often under enemy fire and dig tunnels under enemy lines which would be filled with explosives.

But it was not to be on the field of battle where Joseph met his sternest test.

When hordes of young men enthusiastically joined up in 1914, the army was faced with a problem. It had to train the hundreds of thousands of volunteers and shape them into fighting men as quickly as possible. Their training facilities had to be expand quickly to cope.

The British Army was traditionally a small professional force and it was not equipped to instruct this number of soldiers. So vast training camps sprung up across the country. One of these was Kinmel Camp in North Wales.

The camp was built from scratch on the land near St Asaph in late 1914 and early 1915 and became the largest military training camp in Wales, even having its own railway.

It was where thousands of soldiers from Wales would have learned how to march, clean their weapon, shoot and prepare to fight on the Western Front. The training trenches can still be seen in the grounds of nearby Bodelwyddan Castle.

It at times wasn’t an especially happy place. It was also known grimly as 'Kill'em Park' because of the dozens of young men who died there from pneumonia and other diseases there.

It is best remembered for the mutiny and which broke out there in March 1919, when 20,000 war-weary Canadian soldiers, angered by their treatment at the end of the war, rioted. Several of their ships home had been cancelled, and were also annoyed that promises that those men who had enlisted first would be sent home first had not been honoured. The disorder lasted for two days and saw five men killed, and 23 injured.

But Newport soldier Joseph Stokes prevented at least one tragedy there by showing great courage and risking his life.

By 1916, conscription had been introduced and alongside the heavy losses the British Army in battles like that on the Somme, it meant the flow of recruits grew stronger.

By October that year, Joseph had reached the rank of Sergeant. The 23-year-old had seen action but was instructing soldiers in how to use the Mills Bomb, or hand grenade.

Recruits would begin their training by throwing inert, or dummy grenades. While outwardly, they looked the part, the metal casing looking famously like a ‘pineapple’ they would be filled with wood.

On the day Sgt Stokes took an officer and two Sappers, or Royal Engineers to the training trenches, the grenades they had were real.

Known as the ‘Mills bomb’ the hand-thrown devices were the first modern fragmentation grenades used by the British Army.

William Mills had only began making them a year before, but they quickly became invaluable weapons in trench warfare.

Creating blast for a radius of around 100 yards (90 metres) they would be deadly in the enclosed world of a trench.

A competent thrower was said to be able to hurl his bomb 50 feet (15 metres) but the grenade could throw lethal fragments farther than this.

Sgt Stokes stood at the rim of the trench ready to instruct the three soldiers with their weapons in the pit below.

One of the soldiers stood to throw the grenade. As he had been taught, he pulled the pin from the top of the device. This would release a lever, which would be held tight to the grenade until he let go with his hand and it was thrown. As soon as this was released it would allow a spring-loaded plunger to strike the firing pin inside. This would create a small spark which would light a fuse which in turn would light a detonator. This would finally ignite the explosives within the grenade.

All this would take four seconds. But in those four seconds something went horribly wrong. The soldier threw the grenade, but it hit the wall of the throwing pit and fell to the bottom of the trench. If it exploded it would have killed at least the three men inside the pit. The bomb was designed to be used in confined spaces to kill enemy soldiers. The steel casing of the bomb was designed to fragment and tear through human flesh.

And that’s exactly what it would have done to them and perhaps Sgt Stokes had the Newport man not thought and acted so quickly. He leapt into the trench, seized the grenade and hurled it away. It exploded away from the men as they cowered in trench, trembling but still alive.

HONOUR: Sergeant Joseph Stokes with his Mertourious Service Medal

In recognition of his bravery that day, Sgt Stokes was awarded the Meritorious Service Medal (MSM). For much of the First World War, army Non-Commission Officers like Sgt Stokes could be awarded the medal immediately for meritorious service in the field. They could also receive it for acts of gallantry in non-combat situations, like this one. Those who were awarded the medal were also granted an annuity, the amount of which was based on his rank.

The London Gazette, which records the awarding of honours carried the following message for Joseph on the day he was awarded his medal: “His Majesty the King has been graciously pleased to award the Meritorious Service Medal for gallantry in the performance of military duty.”

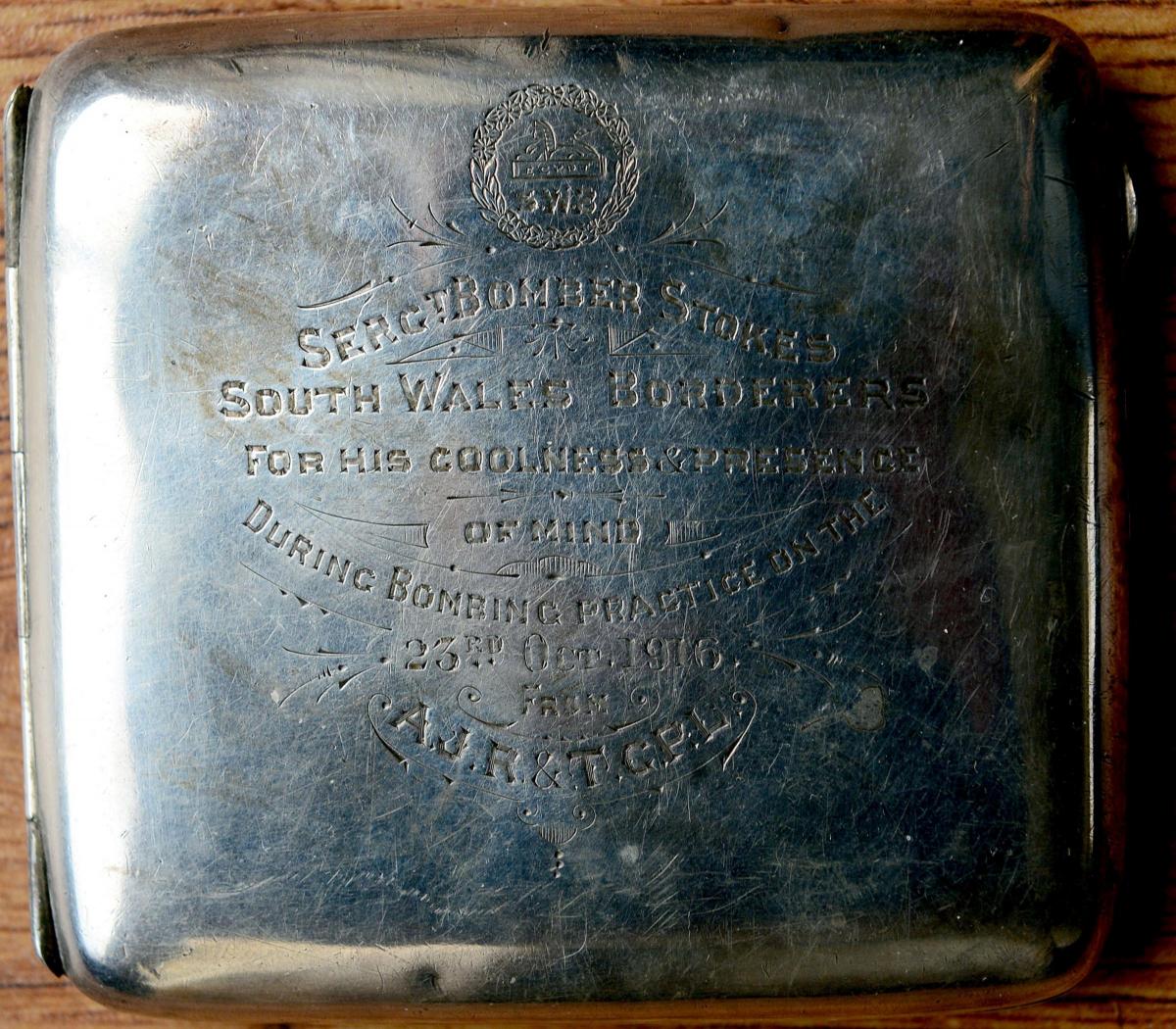

As a special tribute he was presented with a cigarette case from the officer AJ Round whose life he had saved, engraved with the words: “Sergt Bomber Stokes South Wales Borderers for his coolness and presence of mind during bombing practice on 23rd October 1916 from AJR and TCPL”.

MEMENTO: The cigarette case given to Sergeant Joseph Stokes after he saved the lives of three men during grenade practice at a Kinmel Camp in North Wales

Graham is thankful he has this memento of his grandfather’s bravery: “Although he died when I was 18, he never spoke about anything he did, but it makes me very proud.”

The 69-year-old admits he did think about giving it and his grandfather’s medals to the regimental museum in Brecon, but admits: “I’d rather keep them and hand them down. I would never get rid of them.”

Joseph finally left the army in 1920. He went back to work at Lysaghts, but he never forgot that fateful day in North Wales. On his return, he named his house ‘St Asaph’ in honour of the place where he saved three lives and had his brush with death.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here